MONTHLY BLOG 23, WHY DO POLITICIANS UNDERVALUE HISTORY IN SCHOOLS ?

If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2012)

Isn’t it shocking that, in the UK, school-children can give up the study of History at the age of 14? Across Europe today, only Albania (it is claimed) shares that ignoble distinction with Britain. A strange pairing. Who knows? Perhaps the powers-that-be in both countries believe that their national histories are so culturally all-pervasive that children will learn them by osmosis. Perhaps Britons in particular are expected to imbibe with their mother’s milk the correct translation of Magna Carta?

Despite my unease at David Cameron’s embarrassing displays of historical ignorance, my complaint is not a party political one. As a Labour supporter, I’ve long been angry with successive Labour Education Ministers between 1997 and 2010, who have presided uncaringly over the long-running under-valuing of History. (Their lack of enthusiasm contrasts with continuing student demand, which indeed is currently booming).

For critics, the subject is thought to focus myopically upon dates, and upon kings, queens and battles. Students are believed to find the subject ‘boring’; ‘irrelevant’; ‘useless’. How can learning about the ‘dead past’ prepare them for the bright future?

New Labour, born out of discontent with Old Labour, was too easily tempted into fetishing ‘the new’. For a while, the party campaigned under a vacuous slogan, which urged: ‘The future, not the past’. Very unhistorical; completely unrealistic. It’s like saying ‘Watch the next wave, forget about the tides’. Yet time’s seamless flow means that the future always emerges from the past, into which today’s present immediately settles.

It seems that the undervaluing of studying the past stems from a glib utilitarianism. Knowledge is sub-divided into many little pieces, which are then termed economically ‘useful’ or the reverse. Charles Clarke as Labour Education Minister in 2003 summed up this viewpoint. He was reported as finding the study of Britain’s early history to be purely ‘ornamental’ and unworthy of state support. In fact, he quickly issued a clarification. It transpired that it was the ‘medieval’ ideal of the university as a community of scholars that Clarke considered to be obsolescent, not the study of pre-Tudor history as such.1

Yet this clarification made things worse, not better. Clarke had no sympathy for the value of open-ended learning, either for individuals or for society at large. The very idea of scholars studying to expand and transmit knowledge – let alone doing so in a community – was anathema. Clarke declared that Britain’s education system should be designed chiefly to contribute to the British economy. It was not just History, he implied, but all ‘unproductive’ subjects that should be shunned.

The well-documented reality that Britain’s Universities have an immensely positive impact upon the British economy2 was lost in the simplistic attempt to subdivide knowledge into its ‘useful’ and ‘useless’ components.

By the way, it’s this sceptical attitude which has pressurised the Universities, much against their better judgement, into the current Research Excellence Framework’s insistence on rating the economic impact of academic research. An applied engineer’s treatise on How to build a Bridge becomes obviously ‘useful’. But a pure mathematician’s proof of a new theorem seems ‘pointless’.

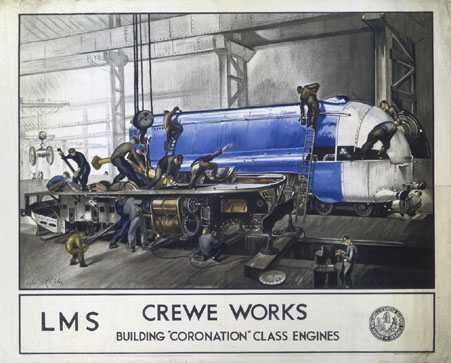

How does contempt for learning originate in a political party whose leaders today are all graduates? It seems to stem from an imaginary workerism. Politicians without ‘real’ working-class roots invoke a plebeian caricature, as a sort of consolation – or covert apology. Give us the machine-tools, and leave effete book-learning for the toffs! They can waste their time, chatting about ancient Greece but we can build a locomotive.

|

Illustration 1: The male world of skilled railway engineering, proudly displayed in a 1937 poster from Crewe © National Railway Museum, 2012 |

Such attitudes, however, betray the earnest commitment of the historic Labour movement to the value of learning. From the Chartists in the 1830s, the Mechanics Institutes, the Workers Educational Society, the trade unions’ educational programmes, the great tradition of working-class autodidacts, the campaigns for improved public education, up to and including Labour’s creation of the Open University in the 1960s, all have worked to extend education to the masses.

| Illustration 2: Mechanics Institutes, like this 1860 edifice from the textile mill-town of Marsden, West Yorkshire, offered education to Britain’s unschooled workers. While not all had the time or will to respond, the principle of adult education was launched. In Marsden this fine landmark building was saved from demolition by local protest in the 1980s and reopened, after restoration, in 1991. © English Heritage 2012 |

No doubt, educational drives require constant renewal. In Britain from 1870 onwards, the state joined in, initially legislating for compulsory education for all children to the age of 10. And globally, similar long-term campaigns are working slowly, as education reforms do, to banish all illiteracy and to extend and deepen learning for all. It’s a noble cause, needed today as much as ever.

Knowledge meanwhile has its own seamless flow. It doesn’t always advance straightforwardly. At times, apparently fruitful lines of enquiry have turned out to be erroneous or even completely dead ends. Many eighteenth-century scientists, like the pioneer Joseph Priestley, wrongly believed in the theory of ‘phlogiston’ (the fire-principle) to explain the chemistry of combustion and oxidisation. Nonetheless from the welter of speculation and experimentation came major discoveries in the identification of oxygen and hydrogen.3 Today, it may possibly be that super-string theory, which holds sway in particle physics, is leading into another blind alley.4 But, either way, it won’t be politicians who decide. It’s the hurly burly of research cross-tested by speculation, experiment, debate, and continuing research that will adjudicate.

There’s an interesting parallel for History in the long-running debates about the usefulness of knowledge within mathematics. The ‘applied’ side of the subject is easy to defend, as constituting the language of science. ‘Pure’ maths’ on the other hand …? But divisions between the abstract and the applied are never static. Some initially abstruse mathematical formulations have had major applications in later generations. For example, the elegant beauty of Number Theory, originally considered as the height of abstraction, did not stop it from being later used for deciphering codes, in public-key cryptography.5

On the other hand, proof of the infinity of primes has (as yet) no practical application. Does that mean that this speculative field of study should be halted, as ‘useless’? Of course not.

My argument, in pursuing the ‘usefulness’ debates, seems to be drifting away from History. But not really. The mind-set that deplores the ‘useless’ Humanities would also reject the abstraction of the ‘pure’ sciences. But try building a functioning steam locomotive, without any knowledge of history or of formalised mathematics or of the science of mechanised motion, let alone the technology of iron and steel production. It couldn’t be done today. And we know from history that our ever-inventive ancestors didn’t do it in the Stone Age either.

1 Charles Clarke reported in The Guardian, 9 May 2003, with clarification in later edition on same date.

2 The Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE) commissioned an independent report, which calculated that Britain’s Universities contributed at least £3.3bn to UK businesses in the 2010-11 academic year, as part of a much wider economic impact, both direct and indirect: see www.hefce/news/newsarchive 23 July 2012.

3 J.B. Conant (ed.), The Overthrow of Phlogiston Theory: The Chemical Revolution of 1775-89 (Cambridge, Mass., 1950).

4 For criticisms, see L. Smolin, The Trouble with Physics: The Rise of String Theory, the Fall of a Science, and What Comes Next (New York, 2006); and P. Woit, Not Even Wrong: The Failure of String Theory and the Search for Unity in Physical Law (2006).

5 See the debates after G.H. Hardy’s case for abstract mathematics in his A Mathematician’s Apology (1940): see ‘Pure Mathematics’ in www.wikipedia.

- My November Blog will discuss the relevance of History not only for economics but also for civics.

- And my December Blog will consider how to ensure that all students study History to the age of 16.

For further discussion, see Twitter

To read other discussion-points, please click here.

To download Monthly Blog 23 please click here

Did the ancient University really lack trust in its own staff and its invited external examiner? In this case, common sense prevailed; and, after a protest, the instruction was withdrawn.

Did the ancient University really lack trust in its own staff and its invited external examiner? In this case, common sense prevailed; and, after a protest, the instruction was withdrawn.

Unfairness is written into the proposed contract from the start, by asking the elected members to attend a specified percentage of all public meetings in their constituencies. Those whose political patches contain many residents’ associations, neighbourhood watches, and other local gatherings will be required to jump over a much higher hurdle than those in sleepy Clochemerles, where nothing happens.

Unfairness is written into the proposed contract from the start, by asking the elected members to attend a specified percentage of all public meetings in their constituencies. Those whose political patches contain many residents’ associations, neighbourhood watches, and other local gatherings will be required to jump over a much higher hurdle than those in sleepy Clochemerles, where nothing happens.

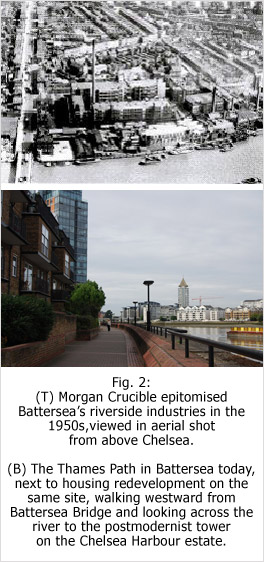

Okay, so not everywhere can look like Venice. Cities have to adapt and change. Venice itself is not immune from innovations. Yet, in the relentless processes of urban development, much more effort is needed to save each place’s distinctive identity – and to introduce or reintroduce such qualities, if they have been lost. If every omni-urban scene looks like every other omni-urban scene, humans have collectively lost something vital.

Okay, so not everywhere can look like Venice. Cities have to adapt and change. Venice itself is not immune from innovations. Yet, in the relentless processes of urban development, much more effort is needed to save each place’s distinctive identity – and to introduce or reintroduce such qualities, if they have been lost. If every omni-urban scene looks like every other omni-urban scene, humans have collectively lost something vital. But my partner saw this image on screen, grinned, and said ‘Great’. I suspect that he was trying to annoy me, although this building is not in fact my personal nomination for the world’s architectural black-spot. Anyhow, a much more important consideration would be to understand the impact of these buildings upon the immediate locality and the wider city environment – and what visitors and locals think in reality.

But my partner saw this image on screen, grinned, and said ‘Great’. I suspect that he was trying to annoy me, although this building is not in fact my personal nomination for the world’s architectural black-spot. Anyhow, a much more important consideration would be to understand the impact of these buildings upon the immediate locality and the wider city environment – and what visitors and locals think in reality. • A musical focus. The Vauxhall Gardens in their prime attracted open-air audiences for summer evening concerts of song and music at both popular and classical levels. Now London has many specialist venues and the bifurcation between high-brow and low-brow can’t easily be undone. But why should the area not host a musical venue of some sort? Maybe a low-cost hall for hire? Plus a link from the Proms in the Park to Vauxhall where London’s open-air summer concerts began?

• A musical focus. The Vauxhall Gardens in their prime attracted open-air audiences for summer evening concerts of song and music at both popular and classical levels. Now London has many specialist venues and the bifurcation between high-brow and low-brow can’t easily be undone. But why should the area not host a musical venue of some sort? Maybe a low-cost hall for hire? Plus a link from the Proms in the Park to Vauxhall where London’s open-air summer concerts began?

This illustration flatters the proposed Market Towers. The sky is deep blue, shading to lighter sky and lights at ground level. The Towers seem to cast no shadows. The surviving Grade I listed building at their feet (centre R) is merged into the background, foretelling its coming obscurity. The traffic at a major traffic interchange is strangely reduced to give the picture harmony. The struggling commuters battling through the wind funnel at the feet of high-rise buildings by the exposed riverside don’t exist. Bah! Humbug! And … more anon.

This illustration flatters the proposed Market Towers. The sky is deep blue, shading to lighter sky and lights at ground level. The Towers seem to cast no shadows. The surviving Grade I listed building at their feet (centre R) is merged into the background, foretelling its coming obscurity. The traffic at a major traffic interchange is strangely reduced to give the picture harmony. The struggling commuters battling through the wind funnel at the feet of high-rise buildings by the exposed riverside don’t exist. Bah! Humbug! And … more anon.

Alongside conscious efforts of memory cultivation, many framework recollections – such as knowledge of one’s native language – are usually accumulated unwittingly and almost effortlessly. Deep memory systems constitute a form of long-term storage. With their aid, people who are suffering from progressive memory loss often continue to speak grammatically for a long way into their illness. Or, strikingly, songs learned in childhood, aided by the wordless mnemonic power of rhythm and music, may remain in the repertoire of the seriously memory-impaired even after regular speech has long gone.

Alongside conscious efforts of memory cultivation, many framework recollections – such as knowledge of one’s native language – are usually accumulated unwittingly and almost effortlessly. Deep memory systems constitute a form of long-term storage. With their aid, people who are suffering from progressive memory loss often continue to speak grammatically for a long way into their illness. Or, strikingly, songs learned in childhood, aided by the wordless mnemonic power of rhythm and music, may remain in the repertoire of the seriously memory-impaired even after regular speech has long gone. And I am not alone. Discovering faults in memory is a common experience. It’s a salutary warning not to be too cocky. Had I been relying upon my unchecked memory when speaking in the witness box, this central error would have discredited my entire evidence. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, as the Roman legal tag has it: wrong in one thing, wrong in all. In fact, the dictum is exaggerated. Errors in some areas may be counter-balanced by truths elsewhere. Nonetheless, I have drawn one personal conclusion from my mortifying discovery. If I’m ever again invited to give testimony on oath or in an on-the-record interview, I will do my homework thoroughly beforehand.

And I am not alone. Discovering faults in memory is a common experience. It’s a salutary warning not to be too cocky. Had I been relying upon my unchecked memory when speaking in the witness box, this central error would have discredited my entire evidence. Falsus in uno, falsus in omnibus, as the Roman legal tag has it: wrong in one thing, wrong in all. In fact, the dictum is exaggerated. Errors in some areas may be counter-balanced by truths elsewhere. Nonetheless, I have drawn one personal conclusion from my mortifying discovery. If I’m ever again invited to give testimony on oath or in an on-the-record interview, I will do my homework thoroughly beforehand.

In the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, the response in Britain was not so drastic. I personally wasn’t so blind about the faults of the Soviet system. And I was not a member of the British CP, so couldn’t resign in protest. Nonetheless, the general effect was dispiriting. The political and cultural left,1 which at that time were still in synchronisation, were angered but also depressed.

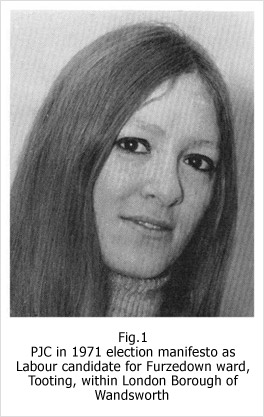

In the aftermath of Czechoslovakia, the response in Britain was not so drastic. I personally wasn’t so blind about the faults of the Soviet system. And I was not a member of the British CP, so couldn’t resign in protest. Nonetheless, the general effect was dispiriting. The political and cultural left,1 which at that time were still in synchronisation, were angered but also depressed. So 1968 was an educative moment for me. Vague utopianism had to be rejected as much as totalitarianism. Indeed, utopianism had to be treated with even more suspicion, since it seemed the more seductive. The answer – between brute force and empty rhetoric – had to be more humdrum and more realistic. In company with my partner Tony Belton, I became more active within the Labour Party. In 1971, we were both elected as councillors in the London Borough of Wandsworth. The outcome of that experience also proved to be stimulating but far from simple – see my next month’s discussion-piece.

So 1968 was an educative moment for me. Vague utopianism had to be rejected as much as totalitarianism. Indeed, utopianism had to be treated with even more suspicion, since it seemed the more seductive. The answer – between brute force and empty rhetoric – had to be more humdrum and more realistic. In company with my partner Tony Belton, I became more active within the Labour Party. In 1971, we were both elected as councillors in the London Borough of Wandsworth. The outcome of that experience also proved to be stimulating but far from simple – see my next month’s discussion-piece.

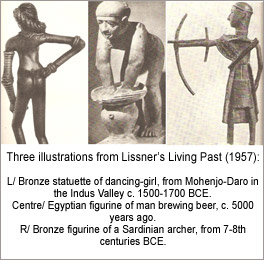

I remember reading this work with fascination as a teenager in the 1960s and then letting it lie fallow, as it was so far removed from anything in the normal History curriculum, either at school or university.

I remember reading this work with fascination as a teenager in the 1960s and then letting it lie fallow, as it was so far removed from anything in the normal History curriculum, either at school or university. Above all, the text conveyed the implicit assumption that, with historical effort and study, one human could understand, even if not approve, the culture of any other, anywhere around the world – and at any time.

Above all, the text conveyed the implicit assumption that, with historical effort and study, one human could understand, even if not approve, the culture of any other, anywhere around the world – and at any time.