If citing, please kindly acknowledge copyright © Penelope J. Corfield (2020)

|

Vera Bácskai in 2016 in image taken from Youtube Interview in Hungarian:

© Tabudöntök: Bácskai Vera a Petőfi Körrol (2016)

|

Behind the invariably calm, genial and ecumenical welcome accorded by Vera Bácskai to her many friends and colleagues around the world, there was a hit of something darker. ‘Melancholic’ would not be the right word. Nor would ‘bleak’. Those adjectives are far too negative. A better description would be a hint of inner stoic fortitude, indicating someone, who had faced a complex trauma of political failure and personal deprivation at the age of 26, and come through determinedly and, eventually – but only after the passage of many years – triumphantly.

Is it saying too much, to detect all that in the personality of Vera Bácskai? I don’t think so. We live our own personal histories, which are imprinted in our personalities. Vera not only lived through turbulent times but, for a moment in November 1956, she herself was literally present in the eye of the Hungarian storm, when the Soviet army invaded Budapest.

For my part, I first met Vera Bácskai in the later 1980s, through our shared interests in urban history. We talked animatedly about research, politics, our mutual friends, our families, and our shared interests in classical music and detective stories. Not for a moment did Vera allude to her own past history, whether to exult at her youthful daring or to complain at the outcome or simply to convey basic information. She was affable but reserved. I later realised that this tough, deep silence was Vera’s way of coping with trauma. As a response, it is a well known one among veterans, particularly in earlier generations, who have faced bitter experiences in wartime or other forms of conflict.2

In the early 1950s, Vera Bácskai had been one of many youthful enthusiasts in Hungary for liberal/radical explorations of socialism and internationalism. She joined an influential network of like-minded activists, known as the Sándor Petőfi Circle.3 This debating club was so named after their national poet, the hero of the 1848 Revolution who died young in 1849 at the age of twenty-six.4 ‘Liberty and love/ These two I must have’ … Petőfi’s most famous verse couplet represented the romance and the enthusiasm of the movement. It was part of the flowering of national and cultural idealism which defined itself after World War II as renewing socialism – but was not so defined by the Soviets. The army was dispatched to crush what was termed the Hungarian Uprising or Revolution,5 just as in 1968 it was sent into Czechoslovakia to crush the Prague Spring.

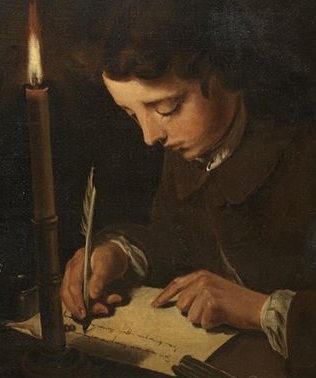

Faced with absolute crisis on the streets of Budapest, the Hungarian leadership with a core of supporters retreated for safety into the Yugoslav Embassy (now the Embassy of the Republic of Serbia). It is a solid building at the conjunction of two major roads, Andrássy út and Dózsa György út, sited immediately opposite to what is now the imposing Heroes Square, celebrating the historic Magyar origins of Hungary. The situation then was tense and utterly chaotic, as bullets flew. The Hungarian Prime Minister, Imre Nagy, and numerous close colleagues in government, were ‘persuaded’ into leaving the Embassy and were promptly taken into captivity by the Soviet army. Most were immediately sent into exile, although the Hungarian leader, Imre Nagy (1896-1958), was recalled to Budapest, where he was arrested, put on trial and executed in 1958.6 (Today the confrontation between the Soviets and the Hungarian insurgents is commemorated by a modest plaque on the front wall of the building).

|

Fig.2 The Serbian (formerly Yugoslav) Embassy in Budapest, showing the windows of the first floor room into which the defiant leaders of the Hungarian government and key supporters had retreated, before they were taken into captivity by the Soviet Army.

Photo © Tony Belton 2019

|

Among the Hungarian activists who had retreated with Imre Nagy into the Embassy was the young Vera Bácskai. She too was sent into exile at Snagov in Romania, a rural commune 40km north of Bucharest. The move abruptly separated her from her very young daughter without a chance of saying farewell. They did not meet again for several years. Not surprisingly, that break caused Vera feelings of acute guilt and anxiety; and it also strained her relationship with her husband, Gábor Tánczos (1928-79), who had been secretary of the Petőfi Circle and a fellow activist. In 1958 he was sentenced to fifteen years in prison, before being released under an amnesty in 1963. However, these were not matters to which Vera ever alluded in any detail. She buried deeply both her political disappointment at failure in 1956 and her responses to the personal and familial difficulties which followed.

Once, when we were discussing the impact of ‘Hungary 1956’ upon left-wing intellectuals across Europe, I referred to the tensions between the British Communists as they disagreed upon how to respond to news of the Soviet intervention My uncle, the Marxist historian Christopher Hill, found that this event triggered a particularly torrid and unhappy era in his life. He opposed the Soviet move but he hated the disagreements with old comrades, as they argued over how to democratise the British Communist Party. When they failed, many, like Hill himself, then took the wrenching decision to leave the CP. This crisis followed a sad period in his life when his first marriage had disintegrated; and his deeply religious parents were aghast that their much-loved son was getting a divorce, at a time when such break-ups were regarded as dangerous assaults upon societal harmony. All these problems seemed to fuse into a personal and political maelstrom.7 As I spoke, Vera listened intently. And then she remarked, flatly and without emotion: ‘But this is normal, Penny’. It was an understated declaration of: ‘Me too’, but again without vouchsafing any personal details.

From the crisis of 1956 and its aftermath, Vera emerged with strengthened qualities of stoicism, dignity, self-sufficiency and resilience. These traits underpinned her charm and cheerfulness throughout. Perhaps one might speculate about her past of inner tensions from her heavy smoking, which remained a life-time habit long after she realised that it was medically harmful. Be that as it may, Vera’s way of coping with trauma worked admirably well for her. She had no need or desire to wear her heart on her sleeve.

Then in 1958 Vera was reprieved from exile and returned to Hungary. She was at that time banned from teaching. So she found a job in the Budapest Archives. The change was initially regarded as something of a come-down for a brilliant young scholar, who had studied Marxist theory and history in Russia. It provided, however, an intellectual lifeline. Vera transformed herself into an archive historian, with all the strengths which that implied. She learned to read old German, old Hungarian and Latin; immersed herself in the primary sources; and began to write an updated urban/social history that was at once knowledgeable and theoretically informed, yet without Marxist dogma.

Moreover, Vera linked her documentary expertise with topographical understanding. She knew her Budapest. And as Hungary began to open contacts with the wider world in the 1980s, visiting scholars were taken by Vera on guided walks through the old city, to see ancient housing, old churches of many denominations, Turkish baths, an old travellers’ inn with spacious stabling, and a half-built-over but surviving section of the old Pest city walls. The flavour of her work at this time was conveyed in an interview with her in 1996, which I undertook for the Journal of Urban History.8 A characteristic remark on her part stated that: ‘I did not try to be fashionable’.9 It was in this interview that she first explained to me, in very brief and deadpan style, the events of 1956 which led to her exile. I was very surprised at this information and, as I learned later, so were a number of her colleagues at Budapest’s Eötvös Loránd University, where she had eventually gained an academic post in 1991.

International links and international admiration for Vera’s work in due course began then to multiply. By the 1990s, she had become an inspirational figure both within and outside Hungary. Her role as a linchpin of the flourishing European Association for Urban History (founded 1989) was reflected in her election as President in 1996. Indeed, she remained deeply satisfied by her work as an academic; and by her close relationship with her daughter Éva and her two spirited grand-children Gergely (Gergõ) and Judit.

At no time did Vera display any interest in a return to politics. Even after the Hungarian regime change in 1989, when many of her earlier associates either returned to politics or (in the case of Imre Nagy) were rehabilitated as national heroes, she did not in any way push herself onto the public stage. Only late in her life (2016) did she did give an important interview on the Petőfi Circle, essentially bearing witness for the historical record.10

Throughout, Vera Bácskai retained her vivid interest in making connections, reaching out to new ideas, new people, new approaches. She believed passionately that knowledge flourishes best with the aid of open exchange and debate. A motif of a circle, composed of many individuals linking hands around the world would well describe her dedicated commitment – from the Petőfi Circle onwards – to an associational life.

Fig.3 Motif: Hands around the World

© WikiClipArt (2019) |

To all these shared debates, Vera Bácskai brought her original research, her genial courtesy, her enjoyment of discussion, her freedom from dogma, her optimism, and her underlying deep resolve. She was a proud patriot in her love for her country and its unique language and heritage. Yet she simultaneously enjoyed the role of Budapest as a cultural hub between East and West.

Vera Bácskai herself embodied Hungary’s long tradition of liberal radicalism, which looks not inwards but outwards. She contributed to a persistent community of people striving to reconcile freedom with fairness, liberty with commitment, meritocratic learning with universalism. I honour her – from my heart as well as from my head – as a sincere friend, a wise scholar, and a brave internationalist.

ENDNOTES:

1 This account has been expanded from personal testimony given on 16 May 2019 as part of a two-day Conference in Tribute to Vera Bácskai, held at the Eötvös Loránd University, Budapest: with special thanks to Dr. Erika Szívós and her colleagues for their effective organisation, to all present for their enthusiastic participation, and to Dr. Erika Szívós again for kindly correcting errors in an initial draft.

2 See e.g. M. Ritter, ‘Silence as the Voice of Trauma’, American Journal of Psychoanalysis, Vol. 74 (2014), pp. 176-94.

3 Details in A.B. Hegedüs and T. Cox, ‘The Petőfi Circle: The Forum of Reform in 1956’, Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics, Vol. 13 (1997), pp. 108-33; and S. Hall, 1956: The World in Revolt (2016).

4 See W.N. Loew, Gems from Petőfi and Other Hungarian Poets, Translated: With a Memoir of the Former (New York, 1881).

5 G. Litván (ed.), The Hungarian Revolution of 1956: Reform, Revolt and Repression, 1953-63 (1996); L. Péter and M. Rady (eds), Resistance, Rebellion and Revolution in Hungary and Central Europe: Commemorating 1956 (2008); P. Lendvai, One Day that Shook the Communist World: The 1956 Hungarian Uprising and its Legacy, transl. A. Major (Princeton, 2008).

6 See variously P. Unwin, Voice in the Wilderness: Imre Nagy and the Hungarian Revolution (1991); K.P. Benziger, Imre Nagy, Martyr of the Nation: Contested History, Legitimacy, and Popular Memory in Hungary (2008); J.M. Rainer, Imre Nagy: A Biography (Budapest, 2002) transl. L.H. Legter (2009).

7 P.J. Corfield, ‘Christopher Hill: The Marxist Historian as I Knew Him’ (2018), in PJC website www.penelopejcorfield.co.uk/Pdf/47. For many different perspectives upon debates within British communism in 1956 and thereafter, see: D. Widgery, The Left in Britain, 1956-68 (1976); [Anon.], The Cult of the Individual: The Controversy within British Communism, 1956-8 (Belfast,1975); M. Heinemann, ‘1956 and the Communist Party’, Socialist Register, 1976 (1976), pp. 43-57; D. McNally, ‘E.P. Thompson: Class Struggle and Historical Materialism’, International Socialism, Vol. 2:61 (1993); T. Brotherstone, ‘1956 and the Crisis in the Communist Party of Great Britain: Four Witnesses’, Journal of Socialist Theory, Vol. 35 (2007), pp. 189-209.

8 P.J. Corfield, ‘A Conversation with Vera Bácskai’, Journal of Urban History, Vol. 25 (1999), pp. 514-35. See also, for her further reflections in Hungarian upon her work as a historian, A. Keszei, ‘“Én kíváncsi történész vagyok”: Interjú Bácskai Verával/ “I am a Curious Historian”: Interview with Vera Bácskai’, Korall, Vol. 1 (2000), pp. 7-18.

9 Corfield, ‘Conversation with Vera Bácskai’, p. 532.

10 Youtube Interview: Tabudöntök: Bácskai Vera a Petőfi Körrol (2016).

For further discussion, see

To read other discussion-points, please click here

To download Monthly Blog 109 please click here

Call it a political RED-GREEN alliance. Call it a loose political RED-GREEN federation. Even a move towards a full-blown RED-GREEN party merger? But enough shilly-shallying. It’s time for action.

Call it a political RED-GREEN alliance. Call it a loose political RED-GREEN federation. Even a move towards a full-blown RED-GREEN party merger? But enough shilly-shallying. It’s time for action.